Changemakers: Common Object Studio

18-Sep-2025

By rooting their industrial design practice in radical transparency and local material ecosystems, Fernando Ramirez and Justin Beitzel – co-founders of Common Object Studio – show how reimagining supply chains can lay the foundation for genuinely regenerative practices.

“To avoid adding to the conflation of regenerative and sustainable,” they note, “we keep our usage of terms fairly tight.”

Interview #13 in the Changemakers series

In this interview, we explore how Fernando and Justin are reimagining the system of furniture manufacturing – by using transparency as a design tool and working within local contexts, they’re seeking to bring us closer to true circularity.

This is the 13th in our Changemakers series – interviews with leaders in sustainable, circular and regenerative approaches in the furniture industry. Our aim is to uncover the nuts and bolts of how each leader is driving change, the potential it holds, and why it matters to the industry.

Fernando Ramirez and Justin Beitzel of Common Object Studio

mebl: Hi Fernando, Hi Justin! Tell us about yourselves and about Common Object Studio.

Fernando Ramirez: We always make the joke that we are product designers who don’t like products – as we're very careful about what and how much we put out in the world. About four and a half years ago, we founded Common Object Studio – with the goal of specializing in sustainable and regenerative design. We are also consultants to companies eager to take bigger steps in those directions.

Initially, our intention was to make furniture that gives back more than it takes. But we realized really quickly that it's the system that has to be rethought. So, we shifted to reimagining a system of making furniture, with an emphasis on regenerative practices.

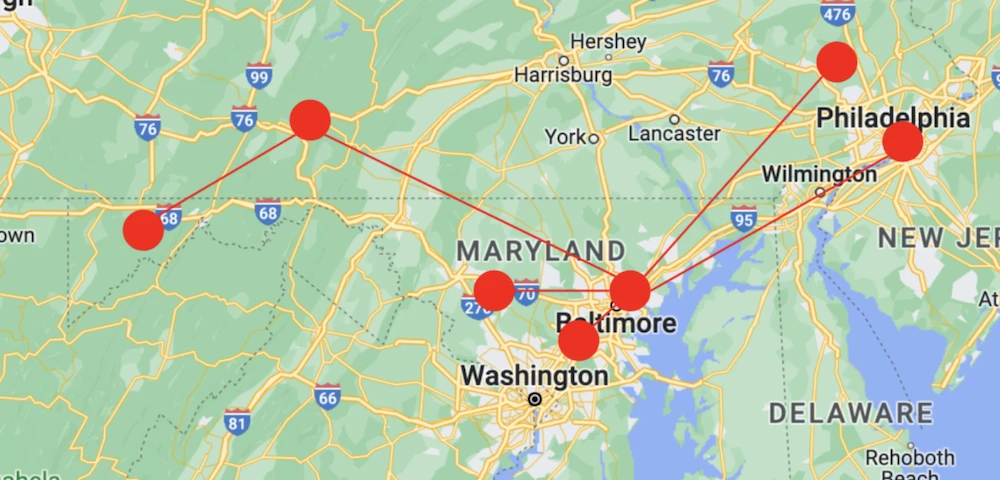

By evaluating the range of industry and resources in a geographic area – and simultaneously assessing its waste, possible material partners, and how to connect those dots – we build compact regional supply chains from the soil up.

This allows us to cultivate connections with regenerative farmers in a specific bio-region, helping them grow and scale while also reducing our own environmental impacts. To date we have developed local supply chains in Maryland and Pennsylvania – and we now have a grant to develop something similar in Michigan. The products we create carry the story of these supply chains.

A map of Common Object Studio’s local supply chains and their interconnectedness across Maryland and Pennsylvania.

mebl: How did your personal paths converge?

Fernando: Justin and I first met when we both went back to school for industrial design. At our core, we are industrial designers, but our diverse backgrounds drive us to think beyond traditional processes.

Our backgrounds are quite a contrast! I grew up in an urban area around Chicago, Illinois – around a lot of hardworking, blue-collar families – a really warm community, largely Mexican and Black. From the very beginning, I just knew that whatever I did, it had to be about building community. Early on, I didn’t even know what that meant, but I knew it was the direction I wanted to go.

That led me to thinking about how the built environment could be healthier, more inclusive. With further exploration, I realized I wanted to understand what happens when things become more user centered. That led me to industrial design.

Justin: I, on the other hand, grew up in Bittinger, a small rural town in Garrett County, Maryland. I was always around a lot of farming. My father was a coal miner and a Mennonite pastor. I had an aunt who painted her entire life but would never call herself an artist. Engineering was seen as a practical path to something bigger while art was encouraged only as a hobby or a side job.

Once in school, I realized how much I love problem solving and seeing users interact with designs. With my engineering background, I was drawn to industrial design, since, to me, it combined engineering and art. As I got deeper into it, I began to understand the true extent to which design has an impact on the planet and communities.

While Fernando and I came to industrial design from different angles, we quickly learned that we shared a vision, values, and a sense of how design could influence the world. After some years working separately – we realized this mission was too big to tackle alone.

Justin and Fernando with one of their local wool suppliers.

mebl: Tell us about the terms regenerative and sustainable in the context of the work you do.

Fernando: We want to keep our usage of those terms fairly tight, to avoid adding to the conflation of the terms regenerative and sustainable. In recent years, the use of ‘regenerative’ has become so blanketed that it has come to mean way too many things. If we're going to contribute to what regenerative means, we often ask: can we find pathways to regeneration?

We see ‘regenerative’ as applying radical intentionality to every piece of a product’s life cycle. We see it as a constant commitment to create and measure positive impact – both environmental and social. When we talk about ‘pathways to regeneration,’ we recognize there will be times we can only focus on one facet or part of a piece of furniture. While that doesn't make the entire product regenerative, it shifts the process in the right direction.

Realistically, the infrastructure needed to achieve a complete ‘closed loop’ – necessary for true regeneration – is not here yet. We want to foster hard discussions about what regeneration really means and what is needed to achieve a closed loop system down the line. By ‘closed loop,’ we’re talking about systems that focus on a circular flow of resources, aimed at keeping materials at their highest utility and value by turning discarded products back into raw materials for production.

Justin: We saw that regenerative agriculture was becoming a movement. It’s clear how farmers can regenerate their land. So we started exploring what regenerative means when applied to the ecosystem of furniture production.

Understory is a collection of stools and space dividers that are 100% bio-based and biodegradable. This collection uses local waste wool from farmers, willow sticks, salvaged wood, and hemp hurd mixed with soda lime.

mebl: What’s a project that best illustrates your approach to regenerative design?

Justin: Our Okaterra furniture collection shows what’s possible in developing a regional supply hub. When an order comes in, the entire supply chain activates: our partners at Open Works in Baltimore, for example, craft the wood components from fallen lumber, while wool sourced from regenerative farms in Maryland and Pennsylvania is processed into felt by small fiber mills. Instead of conventional foam, we use waste wool from these farms as cushioning.

Finally, prior to shipping, we assemble the pieces here in Baltimore. It’s a complete supply chain that runs from soil to finished product. And it's not just for us – it's a system others can tap into, since it could support many more makers and companies than just our own production.

The Okaterra Lounge Chair by Common Object Studio – the finished product and a look at what’s inside.

These kinds of local and regional systems existed for thousands of years before. It's now just about taking the time to do the due diligence needed to set them up again. The vision is bigger than one studio — it’s about showing what’s possible, educating others, and ultimately opening the supply chain to others.

Fernando: A big part of all of this is transparency. Whether or not something carries a certification, we want people to know exactly what it is, where it comes from, and how it was made. We can tell you which tree your chair came from, or even the name of the sheep that provided the wool! As we scale, the details might shift from naming a specific sheep to identifying the region, but the principle remains the same.

You need scale to achieve regeneration. Therefore, the biggest impact lies in large furniture manufacturers understanding the impact these regional hubs can have and starting to produce with us. The more you can sell, the more you could support these really great farmers who are doing this innovative work.

mebl: And how have you integrated your passion for building community?

Fernando: We always look for pathways to take care of communities where production takes place. That could be anything from job training to paying meticulous attention to the experience of workers in a particular company. An example is our work with Public Thread, a non-profit enterprise. We take their collected textile waste and help find the right applications and markets for it. That not only diverts material from landfill but also supports community development around the people making the product.

Justin: To build community means to build skills that are valued in that community. We wrestle with how to do that in a way that is equitable for everyone. Manufacturing always impacts a community – whether it happens locally or elsewhere. That’s why building resilience is so important. It's often overlooked that, in certain regions of the US, the loss of production and skills in building furniture, in upholstery and sewing, also leads to the loss of skills when it comes to the circular principles of fixing and repair.

mebl: With your values-driven commitments, do you ever face tough decisions about taking on more conventional or lucrative projects to help keep your business viable? How do you navigate that?

Justin: In a way, sticking to that principle is self-selecting – the companies we end up working with are the ones who are serious about striving toward regenerative design. We’re really clear that sustainability has to begin before the design process even starts. Companies that contract with us need to make that commitment up front, and then we help them embed that thinking into their products and story.

A lot of our role is helping clients see what’s readily possible. Many companies don’t realize the opportunities at hand in their systems. Sometimes it’s about reconnecting old dots: maybe a relationship from a decade ago leads to a recycling partner who completely changes how a company thinks about its product. Most of the companies we work with, if we can show them a pathway to regenerative design, they will take that initial step.

Fernando: When we enter an engagement with a company, we’re looking to find the right pathways for them. We assess their assets and their pitfalls – what they struggle with. This often results in scalable reinventions of their systems, supply chains, and design outcomes which goes beyond counting carbon – but rather thinking in new ways about how products and companies influence every aspect of our ecosystem.

It’s not only about reducing harm but about helping companies take bigger, more intentional steps toward a future where products actively support people and the planet. If we aim beyond sustainability, at the very least we can get closer to true neutrality.

mebl: Could you share a specific project that illustrates this practice?

Fernando: A good example is BuzziChicle, an acoustic lighting solution designed with no glues, no foam, and built from diverted textile waste. By setting that criteria at the very beginning, the design naturally moved the BuzziSpace project toward a bigger step in their sustainability journey.

Exploration guided by curiosity allows us to turn unconventional ideas into concrete, scalable solutions that give companies real pathways toward better sustainability.

The BuzziChicle uses acoustic material composed of 80% post-consumer denim and 20% virgin polyester, mounted on CARB II and PEFC-certified wood. It contains no adhesives, bonding agents, or foam and is easy to disassemble.

mebl: How do you test for material performance?

Fernando: A big saying for us around the studio is ‘experimentation informs application.’ By working hands-on, we not only understand a material’s properties but also its potential. Some materials might only be viable in small volumes — maybe a thousand units a year — but the only way to scale is to start.

Especially with sustainable materials, which often aren’t ready for mass production, it’s critical to understand where they can realistically be applied first, and build from there.

Justin: The beauty of working so closely with material companies is that it allows for an iterative loop that is exciting for us as designers. Instead of throwing something out when it doesn’t work, you can adjust it together – make it thinner, for example, or add loft, or shift its density.

For our first Terra Lounge, we worked with Natural Fiber Welding in Peoria, Illinois. We used their fully biobased, plastic-free leather alternative and really pushed the material’s limits. We also put it through multiple upholstery cycles with traditional upholsterers giving feedback along the way. Our goal is for all our products to be BIFMA-qualified and surface-tested, but that process is really expensive. For new material companies, that certification process is a huge barrier. Safety and durability matter but I do wish there were better systems to help sustainable material companies get past that hurdle.

Wool from local farms that practice regenerative agriculture is processed by small fiber mills into felt and other batting materials. Waste wool is used as a substitute for foam in cushioning.

mebl: Do you ever face tradeoffs between using local, available materials and making something aesthetically pleasing?

Justin: The hardest part is being willing to adjust. Sometimes the market we thought was right isn’t the one, and we have to either find the market that fits or adapt the product so it works. It always starts with meeting farmers where they are. From there, our role is to connect the dots: what’s the right market for this material, and what kind of design will resonate with that audience? We always think about the system around an object – right now, that points us toward lower-volume, higher-end furniture.

mebl: In the current political and economic climate, do you see opportunities opening up as the tide around climate change flows against many of your core principles?

Fernando: I don't know if we’re seeing direct positive opportunities yet, but we're definitely seeing practitioners committed to sustainability come out of the woodwork - and stronger networks growing as a result. We find ways to work together and quicker. It’s as if we're putting on the armor and getting ready for the fight against disinformation around climate change.

Justin: Being part of the sustainability world, we're having to make sustainability palatable in different ways. Talking in a particular way about climate change appeals to a certain crowd and it completely alienates another. So, for example, with farmers, I often talk about our work in a way that doesn't involve climate change – rather we focus on supporting biodiversity, which doesn’t yet feel political.

We're not changing our principles, but understanding that we need to have different conversations than in prior years.

mebl: What’s next for the studio, and how does regional design and local community factor into your future?

Justin: We’ve been thinking a lot about the concept of “made in my bio region”. What does a chair made in Baltimore look like versus a chair made in New Mexico? They're going to have very different aesthetics and very different materials and cultural manufacturing implications. Understanding and leveraging local knowledge is part of the community we build around production, and it also raises interesting questions about how these regional approaches could reshape the broader industry.

Fernando: Solutions have to connect to local systems. That looks different for every project, but the core is the same: understanding where the product is made, how it’s manufactured, who the skilled labor is, and what partnerships can strengthen a local circular economy.

The grant we received to extend our work to Michigan is another step in this direction. It allows us to explore agricultural waste streams and how they can be scaled into viable products. Our approach starts with building the right partnerships, with regional groups, farm networks, manufacturers, and other community-based non-profits.

By combining our approach to exploration with local collaboration, we can design products that are more sustainable while also creating opportunities for the people and communities who bring them to life.

--> READ more Changemaker Interviews here.