A Brief History Of North American Forests

16-Jun-2021

Series > Reclaimed Wood: Beyond the Basics

Part 2. A Brief History of North American Forests and Reclaimed Wood

In Part 1 of this series, we untangled the terminology of responsibly-sourced wood. Now let’s take a step back to understand the history of forestry and its relationship to the rise of reclaimed wood in the United States. The variety and popularity of reclaimed wood that furniture makers use today is a product of the rich ecosystem of America’s forests: from the Douglas fir to the redwood, each tree holds a unique story. In this article, we hope to shed some light on the swift deforestation of the United States’ original forests and how it led to the modern revitalization of ancient lumber by large furniture companies and independent artisans alike.

The Beginning of American Forestry

According to Reclaimed Wood: A Field Guide, massive old-growth forests had populated the land for millennia before settlers arrived in the United States in the early 1600s. Authors Klaas Armster and Alan Solomon tell the story of how these trees had matured over the course of many centuries, sometimes 500 years, and had been felled sparingly by Native Americans for hunting and farming. In Americans and Their Forests: A Historical Geography, Michael Williams notes that before 1600, the geography of the continental U.S.was made up of 45% ancient forests. These trees had been allowed to grow naturally, producing rich coloring, dizzying concentric rings in their trunks, and strong limbs before being cut down.

“Interior, view of dressed lumber, shed,” 1907, Potlatch Lumber Company, Manufacturers of Fine Lumber: Idaho White Pine, Western Pine and Larch by F.D. Straffin.

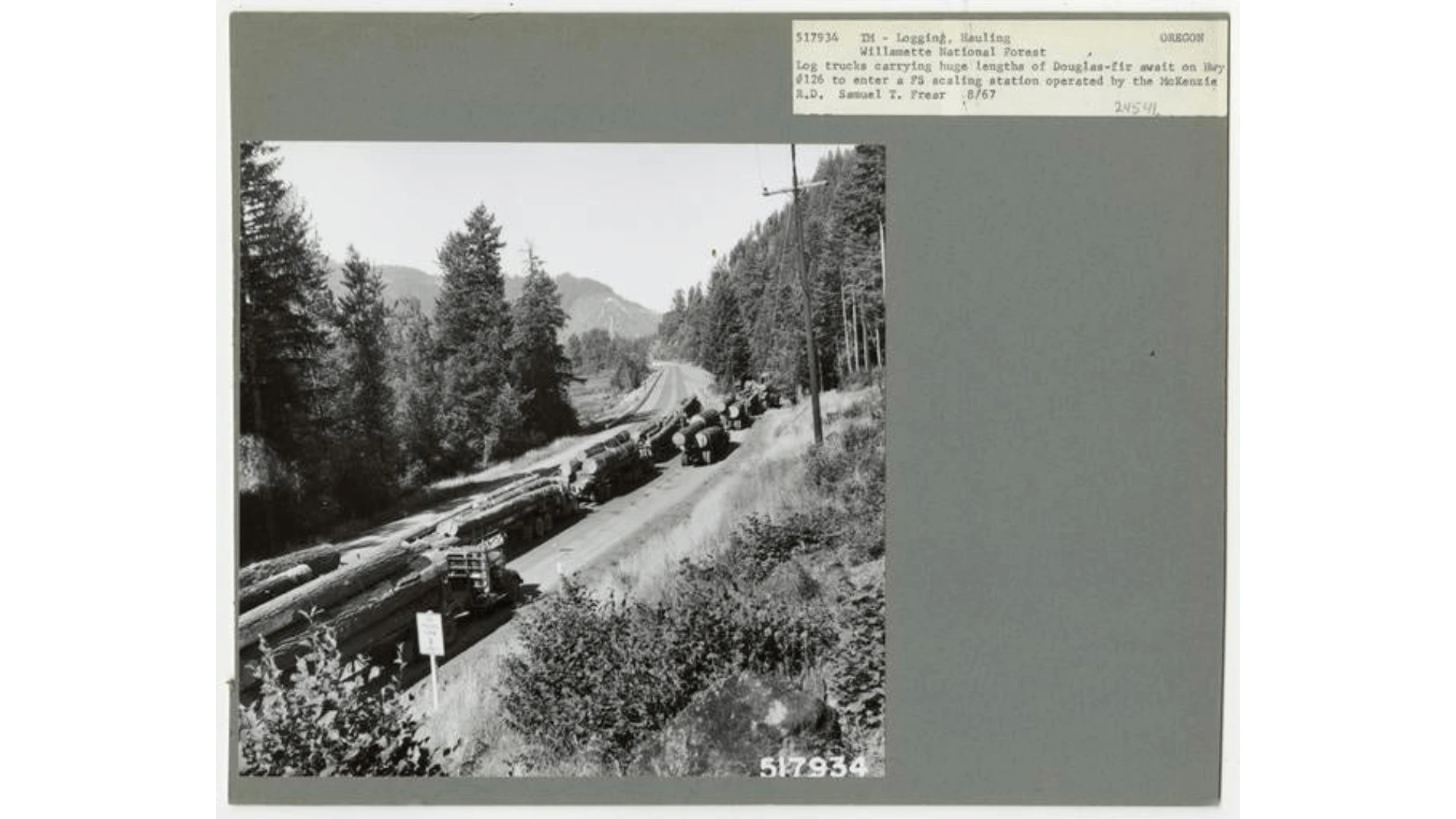

A Wave of Destruction

But by the start of the 17th century, it was clear that, unlike the Native Americans’ sporadic razing of trees, the new inhabitants were going to capitalize on the wealth of resources on a grand scale. In 1620, the Dutch in Manhattan had built sawmills around modern-day New York City to turn ancient eastern white pines into ships, barns, mills, water tanks, and warehouses. By 1830, a third of the lumber in the U.S. came from New York. Quickly, the once fruitful land became a dumping ground of logging waste, stumps, and sawdust. Williams notes that in 1836, a man named James Hall called the U.S. a “wooden country” because of the American need to replace materials such as stone or iron with lumber.

By the mid-19th century, the ancient eastern white pines, as Armster and Solomon note, had been decimated by the Dutch in the northeast.

“White pine log storage--Potlach River--Capacity Four Million Feet,” 1907, Potlatch Lumber Company, Manufacturers of Fine Lumber: Idaho White Pine, Western Pine and Larch by F.D. Straffin.

With the arrival of the Second Industrial Revolution in the late 1800s, the logging industry proliferated across the country, cutting down more and more trees of all varieties. One by one, different regions took up the mantle and started to fell forests. The Great Lakes cut ancient hemlocks, spruces, balsam firs, and red pines. Chicago was well positioned to transport lumber on rivers and lakes to the East. The longleaf pine was also harvested from Texas to Virginia and sent via waterways around the U.S. Mississippi felled ancient Southern pines and Gulf states cut down bald cypresses. Bolstered by the railroad boom, these states, along with other parts of the South and Great Lakes region, could efficiently transport lumber.

The slowest area of the U.S. to harvest old growth forests, as detailed in A Field Guide, was the Pacific Northwest. Indeed, the Douglas fir from this region is only seen in buildings after the early 20th century. The terrain and weather were unconducive to logging and the region was separated from the eastern lumber markets, even with the advent of the Northern Pacific Railway. The building boom following the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897 sped up deforestation as the timber trade exploded. Wood from this area consisted of fir, cedar, hemlock, Sitka spruce, and, of course, redwood.

The old-growth lumber trade ebbed at the beginning of the 1900 along with the near-complete destruction of the ancient forests. This was due to the continued demand for lumber in the “wooden country” as the U.S. relied on logging for expansion. Today, Armster and Solomon explain, only several old growth woods remain and are federally protected. As such, the only way to build with this ancient timber is through reuse.

The Rise of Reclaimed Wood

However, just because there was no old-growth wood left to harvest didn’t mean that people were jumping at the chance to buy reclaimed wood and reclaimed-wood furniture. A Field Guide explains that until the 1950s and 1960s, reclaimed wood was considered “second-hand” or “used”, making it seem dirty and not as good as new lumber. But as early as 1919, magazines were publishing articles that promoted the idea of reusing wood, though lumber taken from old structures was still used for jobs like relining sewers. After the Second World War, Americans started to see new value in reclaimed wood, using it for feature walls and furniture.

A Field Guide cites a few reasons for this transition:

- The growing need for new lumber during the World Wars made reclaimed wood the only available material for builders.

- The hippie movement in the 1960s and 70s introduced recycling centers and co-ops into mainstream society, where reclaimed wood was the cheapest way to live comfortably.

- And the destruction of New York’s Penn Station in 1963, which roused preservationists’ anger across the country.

Photo of “Coast redwoods in area logged about 50 years earlier,” taken circa 1967, California State Library.

Demand for reclaimed wood has continued to grow and now well-made reclaimed wood furniture is prized and very much in style. Grand View Research predicts that the global reclaimed wood industry will grow 4.6% by 2028: from around $50 billion in 2021 to $70 billion. Indeed, IMARC reported that the global reclaimed wood market grew 4% from 2015-2020. Grand View Research also writes that North America accounts for 54.8% of the reclaimed -wood market. The storied history of ancient forests in the United States only adds to the profundity of these trends.

---

By Danya Rubenstein-Markiewicz, mebl | Transforming Furniture

Read the other articles in the Reclaimed Wood: Beyond the Basics series.

References:

Armster, Klaas, and Alan Solomon, Reclaimed Wood: A Field Guide, Abrams Books, 2019.

Fernow, Bernhard Eduard. A Brief History of Forestry: In Europe, the United States and Other Countries. United States: University Press, 1911.

MacCleery, Douglas W.. American Forests: A History of Resiliency and Recovery. United States: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, 1993.

Straffin, F. D. Potlatch Lumber Company, Manufacturers of Fine Lumber: Idaho White Pine, Western Pine and Larch. Spokane, Washington: Inland Printing Company, 1907.

Williams, Michael. Americans and Their Forests: A Historical Geography. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

“Coast redwoods in area logged about 50 years earlier” California Division of Forestry. 1 photographic print on cardboard mount ; 16 3/4 x 13 3/4 in. United States: California State Library, 1967 (?)

“Reclaimed Lumber Market: Global Industry Trends, Share, Size, Growth, Opportunity and Forecast 2021-2026”. United States: IMARC, 2021.

“Reclaimed Lumber Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Application (Flooring, Beams & Boards, Furniture), By End-use (Residential, Commercial), By Region (Asia Pacific, Europe), And Segment Forecasts, 2021 - 2028”. United States: Grand View Research, 2021.

Main photo credit: Logging and hauling operation in Willamette National Forest in 1967 from the National Archives.